I don’t want to sound preachy but the future of mass transport will be based on bicycles. That’s why I laughed heartily when I found this story on Treeghugger a few weeks ago about how a group of cyclists painted five kilometres of bike lanes in a single day. After reading this article I pulled my bike from the garage and planned to take it to a repair shop for a service. I still haven’t taken the bike to the repair shop. In fact, instead of my bike taking up space in my garage, it is now taking up space wherever I left it. Don’t judge me.

The next thought I had was, “Vandalism can be useful”.

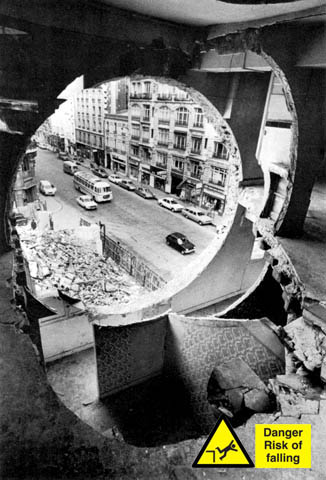

I have often had this thought. Sometimes aloud. Especially when I see tee shirts with ‘ironic slogans’ on them. I’ve mostly had this thought while standing on a train filled to capacity with people who think it sporting to sweat on me at eight in the morning and realising that my only option for relief would be to use my head to break a hole in the wall to generate some ventilation.

Importantly, I do not think this thought in the modern hipster sense that ‘everything is a canvas’ or that ‘city walls can host conversations’. This just perpetuates the illogical idea that everyone is an artist. I mean, how many truly meaningful things are written on walls? The last thing I read on a wall with any semblance of wit was “Lifes to short to sit here to long” (sic).

I approach the subject of vandalism more in terms of urban renovation. While the city walls are not necessarily canvases, I am of the mind that a city is never finished. This is probably a throwback to my ultra suburban upbringing; nearly every house in the area was in the process of renovation or had recently been renovated. Once a piece is completed (a new building, bridge or breakfast nook) it needs to be reviewed and improved upon. A city is the epitome of the perpetual beta.

Now, I’ve never been one to follow Wilson and Kelling’s broken window theory; the idea that if a window is broken and not repaired it will escalate to more broken windows, squatting, drug use, teen pregnancy and other things that Alan Jones rants about. I feel as though the results of their study are too eagerly used to encourage greater scrutiny of individual citizens and therefore normalises technologies of control, such as surveillance. Imagine Gordon Matta-Clark, busy making art by cutting holes in abandoned buildings, only to be followed by a city council worker taking notes about the level of damage done so that it can be repaired.

Imagine, if you would, that the same level of scrutiny and surveillance was applied to the current curses of urban living. City planners could, in essence, observe the areas of dysfunction with regard to transport and reduce the impact on those around them by working at the edges, implementing slight alterations that cumulate to greater social change. Say, helping to reduce congestion in dense urban areas by including bike paths would be a great idea. But, alas, people in elected positions of authority rarely listen to those who elected them.

But the thing about the team from Mexico City that is most interesting is that they used the systems that governments typically use to deliver large scale infrastructure projects. That is, the team took on the planning and physical work promised by their local government, shifting the cost of burden to those who intend to use the lanes (the ultimate user-pay model). They also got through five kilometres in an eight hour day, which means that with the correct funding it would take the team sixty days to complete the desire three hundred kilometres of bike paths (private enterprise is more efficient than government enterprise). Finally, ongoing costs of maintenance would be assumed by the citizens that make the path, meaning that the cost on the government would be virtually nil.

And yet, it is likely that this group will be charged with damage to public property and be called ‘vandals’.

Perhaps it is best if cyclists just make their own bike lanes as required.